Documenting Jazz 2022 gathered colleagues with an interest in jazz studies from diverse backgrounds and contributions from scholars of all career stages, independent and non-academically affiliated scholars and researchers, critics, archivists, librarians, and practitioners to foster an atmosphere of rich interdisciplinary discussion and debate. The theme of this year’s conference was diversity in an interdisciplinary forum that was inclusive and wide-ranging for sharpening awareness, sharing studies and experiences, and focusing debate on the many aspects of diversity in jazz, today, raising the following questions:

- Who gives voice to diversity in the jazz world?

- What does diversity mean in Jazz Studies in particular?

- Does jazz as musical and social practice contribute to intercultural dialogue?

- Has jazz transcended boundaries beyond its sub-cultures?

- Are diversity and inclusion problematic within mainstream education and research,

programs, perspectives, ethics, and methodologies?

- What can we say of jazz practice, its histories, and communities?

As with previous conferences in Dublin (2019), Birmingham (2020), and Edinburgh (2021),

colleagues with an interest in jazz studies and jazz practice from a diverse array of

backgrounds and career stages were invited to debate and discuss jazz in all its myriad forms. While in no way limited to these, the conference committee encouraged individual and joint papers and panels to address the theme of diversity from these points of departure:

1. Jazz and Economic Equity

2. Jazz in Film & Television

3. Jazz as Social Practice

4. Jazz and Technology

5. Jazz and Gender

6. Jazz and Sexuality

7. Jazz and Politics

8. Jazz in the Popular Imagination

9. Jazz and Visual Culture

10. Jazz and Disability

11. Jazz and its Heritage Legacy

12. Jazz and Improvisation

13. Jazz and the Environment/Ecology

14. Jazz and the virtual world/AI

15. Jazz and Wellbeing

16. Jazz including varying ability

17. Jazz and musical diversity

18. Jazz and Aesthetics

19. Jazz as Discourse

20. Jazz and its Emerging Communities

Who gives voice to Jazz? Copyright 2022 Dr. Joan Cartwright

In Queens, New York, from the age of four, I knew what the face of jazz looked like because the notable saxophonist Budd Johnson was my babysitter, when I stayed at his house, waiting for his wife, Bernice Johnson to pick me up for dancing school. By eight, all I knew was that a beautiful ebony woman taught me ballet and her husband practiced jazz riffs from which I learned to scat. So, I never knew, until much later in life, that ballet was a French art and Paul Whiteman was considered the King of Jazz. My first live concert was Duke Ellington at the Apollo, when I was eight. My father’s record collection featured covers with Black musicians on them. How was I supposed to know that white people controlled the music industry and jazz production?

Budd and Bernice Johnson

Each time I converse about the marginalization of women in the music industry, the first question that comes to mind is, “Where were you the first time you heard music?” Invariably, the person reenacts a moment in their childhood home. “No!” I insist, forcing them to think back further to when they first developed ears. Then, they exclaim, “In my mother’s womb!” The conversation proceeds with my conclusion that every person’s mother was the first musical instrument they encountered. The blood rushing through mother’s veins was the sound of strings, the heartbeat was the drum, and she was probably humming or singing. This scenario is undeniable when I share this fact.

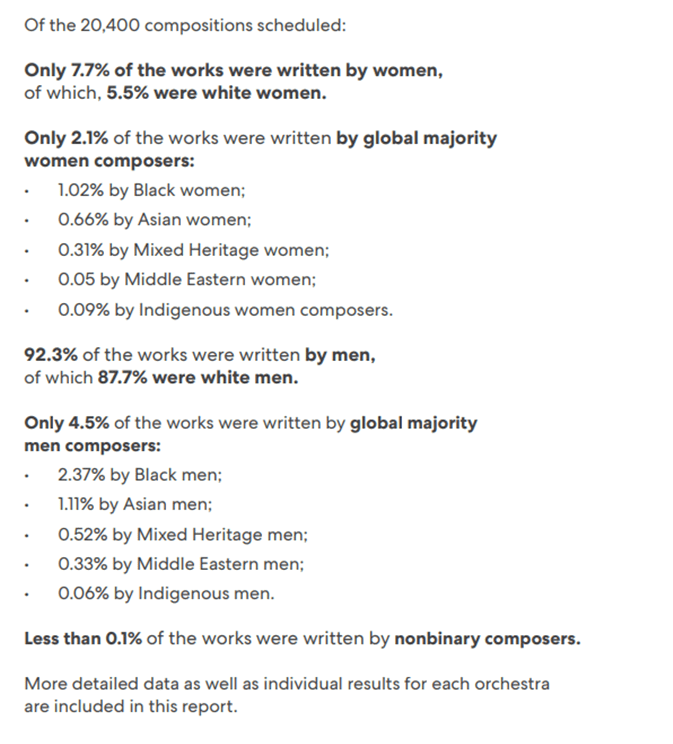

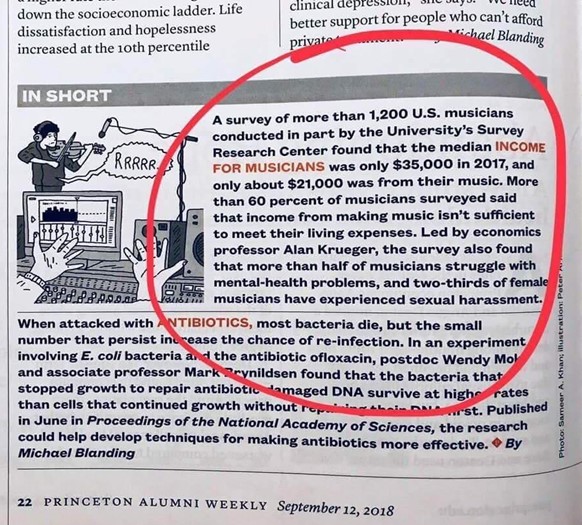

Then. why do women earn less than 15% of the $20 Billion dollar music industry, worldwide? Rather than being a problem, I see an opportunity because 50% of $20 Billion would increase the potential of women musicians to earn by 35%. That is $7 Billion, which would give a lot of women much more income to work with. A study in 2021 by Donne, Women in Music, founded by opera singer Gabriella Di Laccio showed that “the inequality and lack of diversity that our data demonstrates across classical music reflects the lack of opportunity that women face across all musical genres” (Di Laccio, 2022). Moreover, in countless areas of American culture, the contributions of Black women in jazz have been underappreciated for decades (Effinger, 2021).

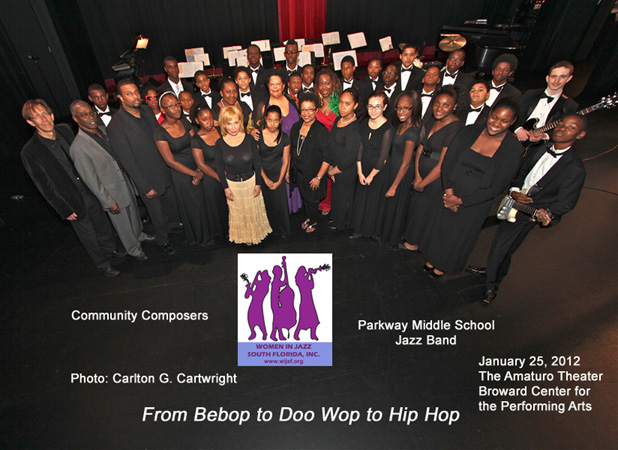

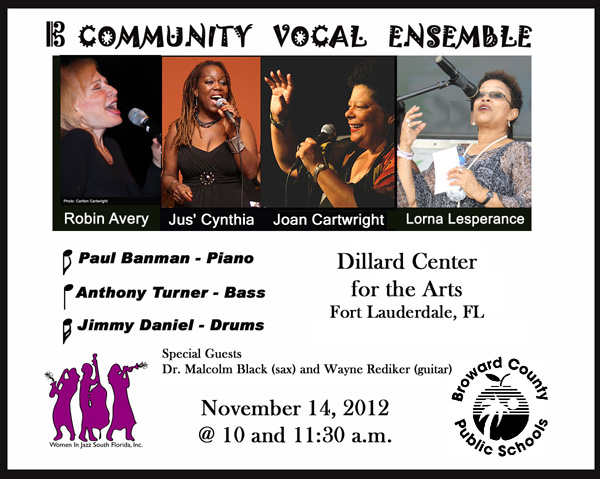

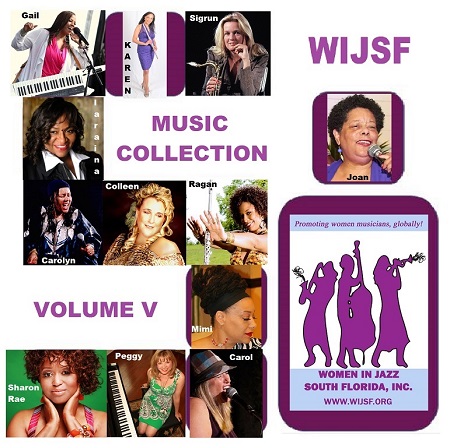

Although I had what I consider to be a charmed life as a jazz singer in the U.S., Europe, Asia, Jamaica, Mexico, Brazil, and many other places, I realized that I had only performed with six women instrumentalists, namely, bassist Carline Ray, one of the Sweethearts of Rhythm, drummer Paula Hampton, the niece of Lionel Hampton. bassist Kim Clarke, and pianists Bertha Hope in New York, Tina Schneider from Germany, and Marion Otten from Holland. This made me pause and wonder where the women jazz instrumentalists were. From 1997, I began documenting their lives on my website in a Jazzwomen Directory that numbers 100 women, today. I produced Gaiafest, A Celebration of Mother Earth with Women in Jazz, in 1998, honoring Dorothy Donegan and Dakota Staton. By 2007, I founded Women in Jazz South Florida, Inc., a nonprofit organization with the mission of promoting women musicians, globally. To date, we have 412 members with 263 musicians. Most are singers but instrumentalists and composers support us and are featured in our monthly newsletters, on my podcast Musicwoman Live, and in our annual publication – Musicwoman Magazine.

When Wynton Marsalis invited Melanie Charles to sing with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, she realized that “the way I interpreted jazz, what Lincoln Center and Juilliard represented when I was a student at the New School, was so far away from actually what the reality is. It is actually rooted in soul” (Effinger, 2021). Norman Mapp’s standard implies this.

Jazz Ain’t Nothin’ But Soul! By Norman Mapp

Jazz is makin’ do with ‘taters and grits,

Standin’ up each time you get hip,

Jazz ain’t nothin’ but soul!

Jazz is livin’ high off nickels and dimes,

Telling folks ’bout what’s on your mind,

Jazz ain’t nothin’ but soul!

Trumpets cussin’ saxophones

Rhythm makin’ love,

People wearin’ fancy clothes,

It’s the voice of my people!

For me, jazz is all the truth to be found,

Never mind who’s puttin’ it down,

Jazz ain’t nothin’ but soul!

Traditionally, the cultural production of Africans has been emulated by European and American musicians without much thought of the implication that the music was stolen like the people who produced it. Jazz was the new cotton crop, harvested, packaged, and sent to market. Up until the 1950s, industrial action by the musicians’ unions on both sides of the Atlantic made it difficult for musicians from the United States to perform in Britain. According to Taylor in 2007, “Through white appropriation and discourses of exoticism or authenticity, Black music has sometimes been translated into a marker of fixed racial difference” (Toynbee, 2013, p. 3). British appropriation of the art form could appear to celebrate the peculiar institution of slavery. In The Heritage Of Slavery In British Jazz Festivals, George McKay declared that

The work is not concerned with ‘slavery heritage tourism’, but rather with heritage and cultural consumption and production at ‘Transatlantic Slave Trade (TAST) related sites. . . . The heritage centers clearly associated with the slave trade that have jazz festivals included Bristol, Cheltenham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Hull, Lancaster, Liverpool, London, and Manchester. (McKay, 2018, p. 5).

However, for McKay, “jazz was formed in, through, or out of the experience of the transatlantic slave trade; it is the sonicity and creative practice of the Black Atlantic, forging a music that has gone on to have global impact” (Ibid.). Ironically, the presence of Black jazz musicians in Britain was wanting because “shifting patterns of migration to the UK, and the fact that Black musicians have always been a minority among jazz performers contributed to this marginalization” (Toynbee, 2013, p. 1) that stems from “the original claim of race discourse about Africans [which] is a lie, namely that they are not fully human” (Toynbee, 2013, p. 2).

Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO, said ‘Jazz makes the most of the world’s diversity, effortlessly crossing borders and bringing people together…. From its roots in slavery, this music has raised a passionate voice against all forms of oppression. It speaks a language of freedom that is meaningful to all cultures” (McKay, 2018, p. 17). Despite the music’s transatlantic formation, Black Atlantic resonances, liberatory claims around improvisation, proud radical history, and innovative impulses, jazz festivals in Britain remain behind the beat (McKay, 2018, p. 34).

Furthermore, jazz musicians “bear continuous witness to frictions between old and new guards, between traditional and radical, bebop and swing, American and European, black and white, or analogue and digital, the argument essentially boils down to one of authenticity and tradition versus the conquering of new frontiers” (Medboe and Dias, 2014, p. 2). Every artistic movement comes from merging and rejecting some of the characteristics of previous movements. “In music, particularly jazz, imitating certain soloists and reinterpreting standardized musical excerpts can lead to the establishment of new musical styles” (Ibid, p. 3).

While “the record deal represented the apex in the progression from amateur to professional musician” (Medboe and Dias, 2014, p. 4), the gatekeepers in the recording industry picked and chose who would be at the top and how high they would rise. Jazz critics like Leonard Feather, Ralph Gleason, and Nat Hentoff, and festival producers like George Wein in America and Claud Nobs in Montreux determined what was good jazz and who would perform it. Mainstays like George Benson, Al Jarreau, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Dianne Reeves, and Santana dominate the festival circuit, today.

In smooth jazz, Brian Culberson, Boney James, and Candy Dulfer overshadow most Black musicians with the exception of Norman Brown, Jonathan Butler, and Gerald Albright. Only one or two Black women entered this arena but remain obscure. Althea Rene (flute) and Jeannette Harris (sax) have a toehold on the smooth jazz industry, while Gail Jhonson performs on keyboards and acts as musical director for Norman Brown. Violinists Regina Carter and Karen Briggs made headway in the global music market. But the ratio of women to men remains 3:16 of featured artists. Of course, singers continue to have more success and notoriety than women instrumentalists. Likewise,

The stability of the industry model, controlled by what evolved into a handful of powerful record companies, by no means represented an open door to most musicians. The few that secured a deal found their artistic ideals at odds with the commercial concerns of paymasters. After all, advances in royalties and promotional budgets had to be recouped and the goal was to appeal to as large an audience as possible. (Medboe and Dias, 2014, p. 5).

According to scholars Medboe and Dias (2014), “musicians [must] create, deliver, and recoup their investments in the digital environment, while sidestepping commercial or artistic frictions with traditional industries.” Today, this “utopian democracy gives a voice and a platform to all creatives, while diminishing the power of industry-appointed gatekeepers and tastemakers. But creative freedom comes at a cost” (Medboe and Dias, 2014, p. 8). Jazz is performed on a plethora of platforms, providing commentary on the human condition and background for a glitzy cocktail party. Its function is social, since it is “a voice of dissent and a champion for change to serving as a place of comfort and familiarity steeped in traditions and fulfilling expectations” (Medboe and Dias, 2014, p. 10).

The marketability of jazz relies on who is spending the most money and what the expected return is. A digital music company Soundstream learned “the importance of the ways in which commercialization ventures place themselves and their products in the market and emphasize the interconnections between developments and the consumers, markets, and investors imagined by the inventors of that technology” (Lehning, 2020, p. 353). When you follow the money, the underlining question becomes “Who gives voice to diversity in the jazz world?”

Voice Work

The forced silence of women has been a subject of concern long before the age of the suffragette. According to Obourn (2012), “The power of voice is a common theme in African American literature and criticism. Enmeshed in a world of enforced silence, African American authors saw voice as a source of personal and political agency” (Cartwright, 2014, p. 8). As in most women’s fiction and feminist literature, the ability to communicate for African American writers heralded “a search for identity and an affirmation of individual selfhood” (Ibid.).

Historically, women were “constructed as women by silencing their access to public speech [with] a ‘split’ in voice: a ‘father tongue’ that speaks in the language of public discourse and social power versus a ‘mother tongue’ that is interlocutionary, conversational, and that ‘expects an answer’” (Ibid.). Speaking out is not an easy task and “political freedom, including freedom of speech, has [not] insured a person of social ability to voice one’s sense of identity” (Ibid.).

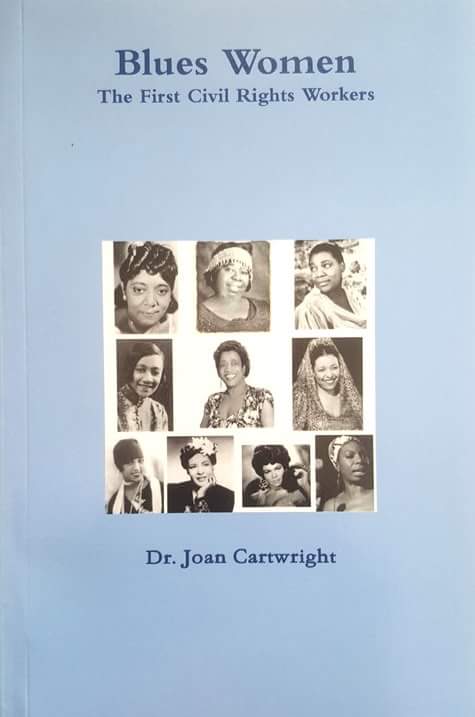

Voice work entails how an idea is politically and socially said or understood. Voice work potentially alters “the ways in which speaking, and hearing can function. It is a term for theorizing a set of political tools that function beyond our individual control” (Ibid.). Vocalists hold a power outside of the realm of instrumentalists and orators because musical accompaniment provides a foundation for their rhetoric. Blues Women stood on top of the list of entertainers and were seen as harmless by producers and town councils that hosted minstrel shows.

Relationally, the minstrel mask worked for whites because it symbolized African Americans as happy and fun-loving. Rhetorically, the minstrel mask worked for blacks, allowing the minstrels to patronize an audience of oppressors, while they complained about their low social status, without fear of being arrested and tortured. However, this process did not extricate them from the horror of their masked existence, and it functioned as a misused symbol (Ibid.). Cultural politician Houston Baker contended that our experience of pleasure and pain is individual, and the realm of the word is miniscule compared to the space of wordlessness in which we exist, therefore, the minstrel mask symbolized the ritualistic repression of the Africans’ sexuality, play, id satisfaction, castration anxiety, and humanity. “It’s mastery,” Houston avowed, “constituted a primary move in Afro-American discursive modernism” (Cartwright, 2009, p. 32). The mask predated African American literature, politics, and open debate, and the Blues women were adept at sporting it. Yet, the music of blacks and women failed to produce economic equity.

Di Laccio’s study of 111 orchestras from 31 countries in 2021-2022, identified the lack of equality and diversity in concert programming. Within this research, diversity referred to gender representation and ethnic representation, exclusively.

But what is the Blues, really? In my estimation, the Blues are the tears of a black woman whose husband is never coming home because he is either lying facedown in a river, after being beaten or shot to death, hanging from a tree with his castrated testicle in his mouth, or headed for points North, never to return. The Blues are the Mother of Jazz, offering a common rhythm and theme for the expression of loss, pain, and sorrow. Although they could not walk through the front door of most performances venues until the mid-20th Century, Black Jazzmen stepped out on the stage with confidence and chops to outplay their white counterparts. So, Jazz, especially Bebop, became a sport of olympian sorts, where playing fast and furious notations became the feat.

While Blues Women offered a voice for their people and community, Jazzmen were bent on proving their individual musical prowess with little concern about their band brothers or the community. Comradery was based on musical harmony or a bandleader who held the group accountable like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Art Blakey. Their bands were like warrior camps out to defeat the enemy – white players. Of course, the lines crossed when certain white musicians either engaged Black musicians or joined the camps of Black bandleaders. The few that come to mind are Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Dave Brubeck, Chet Baker, and Bill Evans.

Meanwhile, few women instrumentalists reached heights in the music industry. Those who did received far less acclaim than their male counterparts. Dorothy Donegan, Hazel Scott, Marian McPartland, Shirley Scott, Shirley Horn, Melba Liston, Dorothy Ashby, and Alice Coltrane managed to make a name for themselves. Yet Scott’s marriage to Stanley Turrentine, Liston’s affiliation to Dexter Gordon, and Alice and John Coltrane were notable exceptions. These women recorded several albums but remained outliers in the jazz equation.

From 1982 to 2022, of 165 National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) Jazz Masters, 24 were women, 141 were men.

For the 41 years of the award, NO WOMAN was awarded in 19 of those years. That is public funding of gender discrimination. Of the 24 women, 10 were singers, 11 played an instrument, and 3 were not musicians (Kirk, Gordon, Oxenhorn).

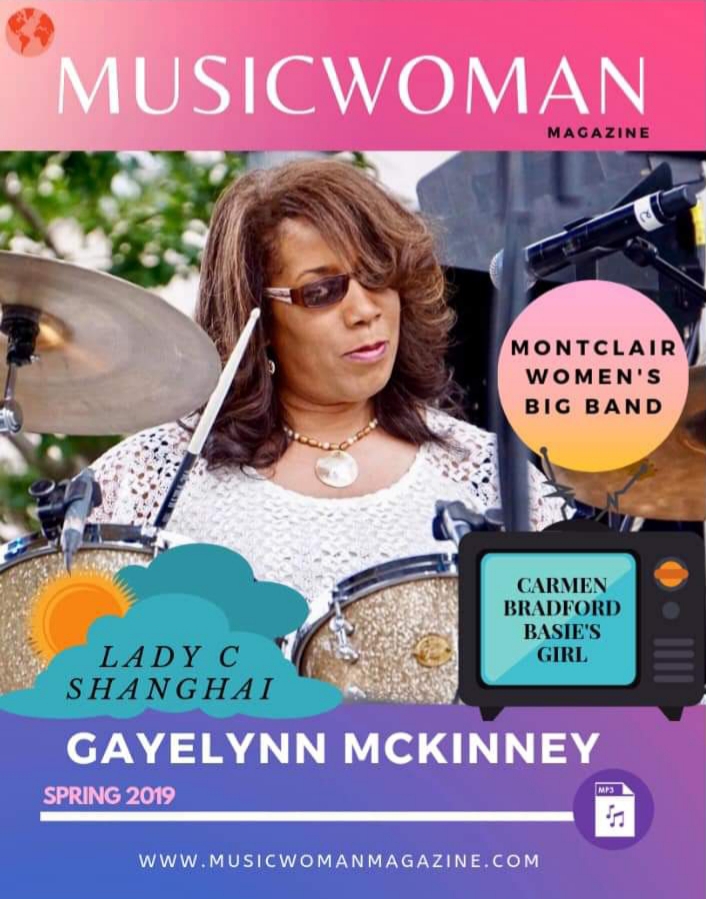

In conclusion, it was profoundly exhibited by several organizations that women compose music regardless of how marginalized they are in the music industry. Olivera Vojna Nesic is an award-winning composer, full professor at the University of Priština in North Kosovo, and Artistic Director of the Association of Women in Music in Kragujevac, Serbia. Nesic promotes music by women composers and artists who perform their works. Since 2003, the Association worked with the Foundation Adkins Chiti: Donne in Musica in Fiuggi, Italy, with the support of the Culture Unit of UNESCO in Venice. The Association is an Honorary Committee member that participates in the Foundation’s projects like the Education and Culture Program and Women in Music Uniting Strategies for Talent (WIMUST). Their composition winners were published in Musicwoman Magazine (2021) edited by Dr. Joan Cartwright and published by Women in Jazz South Florida, Inc. (WIJSF), a nonprofit with the mission of promoting women musicians, globally, and an Honorary Committee member of Donne in Musica.

To date, WIJSF has released eight compilation CDs of women’s music with 76 songs by 58 women composers. These three organizations in Serbia, Italy, and the United States, respectively, have archived the music of hundreds of women composers. Yet, they faced insurmountable economic barriers. The inequity of NEA awards of $25,000 to 141 men vs. 24 women exhibits how much more the music of men is appreciated. The problem is that this award and so much other public funding of musical endeavors comes from taxes paid by women who benefit far less from these monies, which is inequitable and criminal, according to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Therefore, it is incumbent upon women to voice their discontent with the music industry. If is nonsensical for younger women musicians to be faced with the same attitudes their foremothers faced, namely, sexual objectification, omission from major performance opportunities, and lower financial returns than men who play the same instruments and music. In a time when messages go viral in the blink of an eye, it is high time for women musicians to move out into the musical landscape as composers, producers, and royalty and award earners.

On that note, WIJSF celebrates its 262 women musician members, especially Ragan Whiteside who was named, recently, Best Contemporary Smooth Jazz Artists by the Jazz Music Awards. Likewise, we continue to acknowledge Lenore Raphael, a Steinway artist, and so many others who deserve all the accolades and financial support the music industry has to offer.

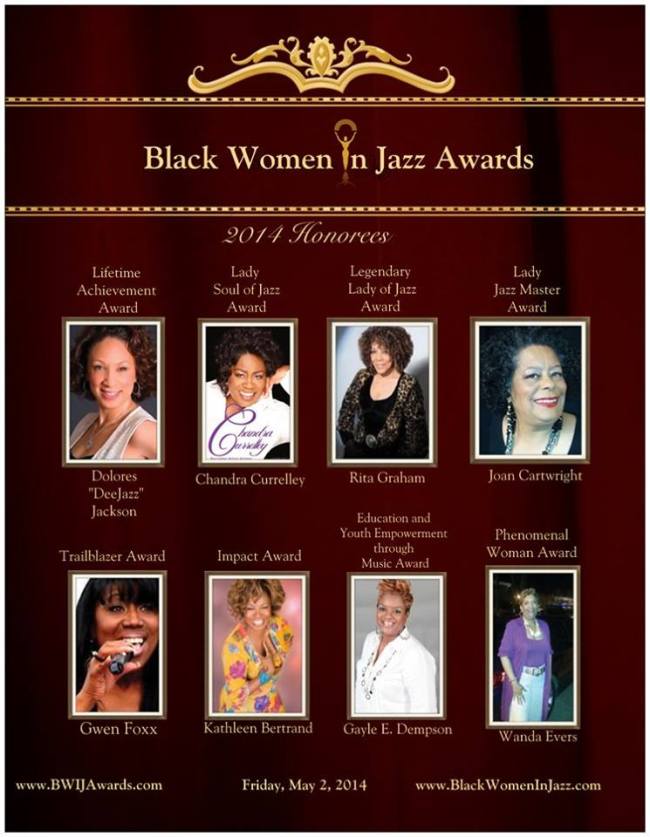

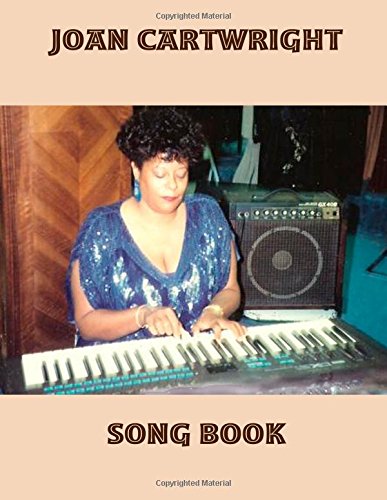

Dr Joan Cartwright is a renowned veteran of the Jazz and Blues stage for 40+ years. She is a vocalist, composer, and author of several books, including her memoir with touring and teaching experiences, and was honored as the first Lady Jazz Master by Black Women in Jazz Awards in Atlanta, GA, in 2014. Her titles include Amazing Musicwomen, So You Want To Be A Singer? and A History of African American Jazz and Blues with interviews of Quincy Jones, Dewey Redman, Lester Bowie, among other jazz musicians and aficionados. In 2007, she founded Women in Jazz South Florida, Inc., a non-profit organization to promote women musicians. In 2022, the organization released its 8th CD of women composers. Dr Cartwright hosts MUSICWOMAN Radio, featuring women who compose and perform their own music at BlogTalkRadio, has two personal CDs Feelin’ Good and In Pursuit of a Melody, and featured as an actor in Last Man and The Siblings, two sitcoms produced by MJTV Network. In June 2022, she incorporated Musicwoman Archive and Cultural Center in North Carolina to preserve the music of women composers and instrumentalists. Visit her websites www.drdivajc.com, www.wijsf.org, and www.musicwomanarchive.com

References

Cartwright, J. (ed.) (2022). Musicwoman Magazine. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/joancartwright/docs/musicwoman_2021_full_document

Cartwright, J. (2014). Blues women: The first civil rights workers. FYI Communications, Inc.

Cartwright, J. (2009). A History of African American Jazz and Blues. FYI Communications, Inc.

Di Laccio, G. (2022). Equality and diversity in global repertoire: Orchestras Season 2021–2022. Retrieved from https://donne-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Donne-Report-2022.pdf

Effinger, S.J. (2022). Melanie Charles knows the impact black women have had on jazz. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/music/melanie-charles-black-women-jazz/2021/11/10/adc8586a-4179-11ec-a3aa-0255edc02eb7_story.html

Lehning, J. (2020). Raising the state of the art. Media History, 26(3), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2018.1487779

McKay, G. (2018). The heritage of slavery in British jazz festivals. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 26(6), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1544165

Medbøe, H., & Dias, J. (2014). Improvisation in the digital age: New narratives in jazz promotion and dissemination. First Monday, 19(10). https://doi.org/10.5210/FM.V19I10.5553

Toynbee, J. (2013). Race, history, and black British jazz. Black Music Research Journal. Vol. 33, No. 1 pp. 1-25 (25 pages). Center for Black Music Research – Columbia College Chicago. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/blacmusiresej.33.1.0001

My life has been inundated with music performance, since I was four years old. By 27, I had borne and raised two children and was on my second divorce. I had the opportunity to finish my Bachelor’s Degree in Music and Communications, in Philadelphia, where I also embarked on my professional career as a vocalist and composer. That was in 1977. By 1990, I owned a small business that placed legal secretaries in law firms. I was doing well but an opportunity arose for me to go to Europe. My children were engrossed in their own families and I was free to go on the road. I began touring in Europe, where I moved in 1994, after completing my Master’s Degree in Communications, in Florida. For eight years, I lived a charmed life touring from country to country, singing Jazz and Blues. In 1996, I moved back to Florida, where I knew I would be challenged to earn the living I earned in Europe. I developed a program to teach K-12 students about women in Jazz. Through grants, I was able to deliver 10 to 20 presentations a year with piano accompaniment. The presentation evolved into a book entitled Amazing Musicwomen.

My life has been inundated with music performance, since I was four years old. By 27, I had borne and raised two children and was on my second divorce. I had the opportunity to finish my Bachelor’s Degree in Music and Communications, in Philadelphia, where I also embarked on my professional career as a vocalist and composer. That was in 1977. By 1990, I owned a small business that placed legal secretaries in law firms. I was doing well but an opportunity arose for me to go to Europe. My children were engrossed in their own families and I was free to go on the road. I began touring in Europe, where I moved in 1994, after completing my Master’s Degree in Communications, in Florida. For eight years, I lived a charmed life touring from country to country, singing Jazz and Blues. In 1996, I moved back to Florida, where I knew I would be challenged to earn the living I earned in Europe. I developed a program to teach K-12 students about women in Jazz. Through grants, I was able to deliver 10 to 20 presentations a year with piano accompaniment. The presentation evolved into a book entitled Amazing Musicwomen.